Review:

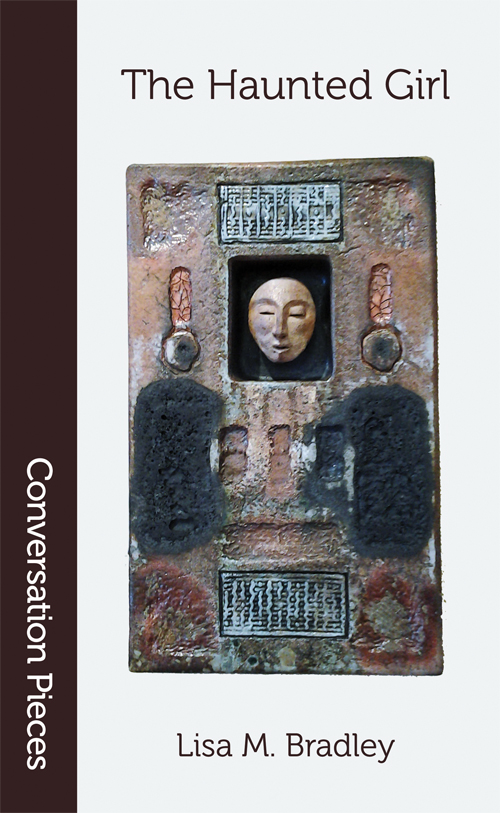

The Haunted Girl, by Lisa M. Bradley

by Alex Dally MacFarlane

I told him I come from a long line of weak women

eager to relinquish gifts, rescind promises,

sacrifice under guise of survival.

– "Teratoma Lullaby"

What, though, is weakness?

There are several threads running through The Haunted Girl. Weakness and its twin, survival. Family. Women. Men. The South Texan heat. The twenty-one poems and five stories are not tightly themed – The Haunted Girl collects fairly broadly from Lisa M. Bradley's work – but the threads are present.

Step under the sun, in "Scavengers", where

We stake our dead to the bleached-bone earth

with picket fence crosses and roadside plastic rose wreaths,

beer can votives and bicycle chain rosaries,

invoking supermarket saints to leave heaven empty.

and, in "Immobility", "I still can't escape your rattlesnake eyes." Bradley's poetry is sharp in its imagery and down-to-earth. At its best, reading it feels like being talked to: there is a person in the poem. Many of the poems are narrative, some at epic length, others at a few pages or a few lines. The cadences of the poem become the cadences of a teller's voice. Meanings do not lie far under those pages, as in "Sun's Stroke", where death is risked in the shade of a snake-man's body to get out of the sun's heat. Anyone who has spent long periods of time far from air conditioning or a cool breeze on a suffocatingly hot day will recognise the desperation, but the metaphor is plain.

Weakness and survival are twins – but like the families in The Haunted Girl, the relationship is not without its complications. Bradley's work returns to the struggle between them. There are poems with titles like "Immobility" and "embedded", the latter an effective ensnarement of looping lines – "in mother's bed / beneath gramma's sheets" – stitching the poem's "I" into bed, into family. The individual survival of a young woman (a teenager, in years) and her lover in "No Patron Saint" after family tragedy – one of the lover's brothers shot in police custody – is especially powerful in the context of louder and louder conversation about repeated police murders of men of colour in the United States. The woman is young, but cannot be. Her role model is the lover's mother, holding up her other sons. Survival is not breaking out of systemic oppression, because how can that be achieved in the wake of one event? But, as I have seen it said, over and over, survival is political. Telling stories, too.

In "Teratoma Lullaby", these twins are made literal in the poem's teratoma twins and made metaphor in turn as a binary star system:

One-third of star systems

are binary or multiple systems.

Fifteen percent of singleton births

began as twins.

The stars in a binary system

are designated primary and secondary.

Either may be a black hole.

One twin, born and years-grown and estranged from the family, and the other, teratoma twin, growing more and more, with a fonder memory of family and a desire to reconnect. "Primary may become secondary…" and lose control of the body:

For this: Let my twin steer this sinking craft

Let him carry my weight for a change

Let me condense enough to live in cliché

and warp the fabric of his space and time

Is this weakness?

In the opening poem, "The Messenger Ensnared", in death – in not-surviving – the fox messenger fights back. In "Castle Lanes", fear, for once, is proved wrong. There are many possibilities in the poems of The Haunted Girl. It is hard, however, to get far from the realities. The titular poem "The Haunted Girl" faces them head-on with anger at the way women are written in many media, anatomised and sexualised and left for dead. The truths of the haunted girl's acted-upon body are laid out in graphic detail – what then?

The two science fictional poems of the collection, "In Defiance of Sleek-Armed Androids" and "Kyrielle for a Cloned Baby", are too near in the future to tell. In the former, it is the broken fractures of humans that appeal, more than the embraces of sleek-armed androids. In the latter, a mother of a cloned baby faces familiar and unsurprising criticism: don't do this! your baby is different! it has no soul in God's eyes!

The Haunted Girl is not concerned with the changed future, but with the realities of today – and how people survive these realities. The frustrated sibling of "Begging Auspices" listens to a sister's complaints about a useless boyfriend and wants to ask, bluntly, why she doesn't deal with the situation differently – but what can you do? Only agree, only be there to listen.

Instead I nod and tsk and suck it up in silence.

Remembering Gram,

I lift my gaze, scan the skies

try to parse each ragged nimbus.

How to make this girl understand…

I have no answer to the question of weakness. It is a fraught term – loaded with judgement, loaded with finality – and I would rather take the poems on their own terms, as individuals, like the individuals within their narratives, who are often not far from the idea of weakness but proceed to survival in their own ways.