Review:

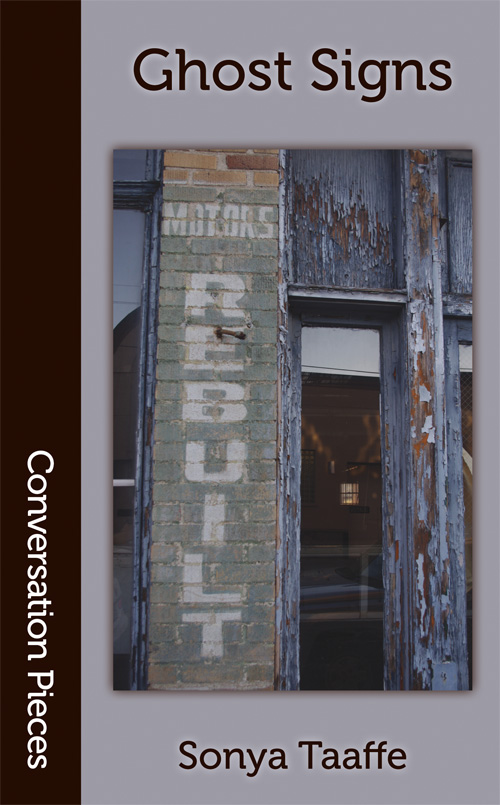

Ghost Signs, by Sonya Taaffe

by Lev Mirov

"Do you know me? The sage-haired child

from the crumbling furrow, the shy lookout

of the apple orchards–"

Cold Spring Calling On, Sonya Taaffe

Sometimes you read a collection of work that feels like it was somehow meant for you. That the author has somehow crept into your heart to bring you poems that speak your language. This is how I feel about the poetry in Ghost Signs, a beautiful collection of poems by Sonya Taaffe, which thread the past and the present together, a dialogue between the living and the dead, following down a few central questions: can the dead speak? Do the dead speak? What, if anything, do they say?

The whole collection is framed as a journey into the underworld and into the world of the dead that lies uncomfortably atop our own, being wooed by Charon (who reappears in The Boatman's Cure, the story that rounds out the collection) and falling in love with many ghosts along the way. This framing helps holds Ghost Signs together as a thematic collection, as well as the strength of the individual poems. Split into two sets, both sets are full of painful, yearning, plaintive questions, the voices of the living reaching back towards the dead. But they are also about what it is like to meet the dead on their own terms, and what they have to say to us when we look back and answer them, in the narrow places where they hang on in a form we can recognize. Some of these interactions are otherworldy and liminal – going to bed with ancient lovers, holding hands with ghosts, bodily possessions – and others seem to engage with the way that the dead speak through the written tradition of what we know about the past – and what we don't know, and can't know.

Many of the poems are in dialogue with Greek mythology and ancient literature. Some of them are about queerness, from Sappho to Alan Turing. There are poems about soldiers, and the things dead soldiers would say to us if we could hear them; poems about the horrors of ancient history and mythology, the silenced voices of tragedies.

A collection like this could feel bleak; almost all the actors are dead, after all, and figures wander on screen the victims of war crimes and battlefields. They ache and burn with loneliness and trauma. Taaffe's poetic "I" wonders: what good comes from meeting the dead? Can we ever understand what has happened before us, or is the very idea of understanding the past pointless? Will we, even under ghostly possession, whispering the words of the dead in that most intimate trespass of the living/dead divide, conclude that "The past will lead on, saying nothing more/than what it has already ceased to say" (Lucan in Averno)?

Taken as a whole, Taaffe's poems suggest not. The dead are only dead, not gone. They will speak for themselves, even when they don't say anything at all – perhaps it is not for us or to us that they are speaking. In the beautiful poem The Color of the Ghost, Taaffe turns to what might be the ultimate answer of her question of whether we can ever really know or understand the dead:

"All night in the sewing room

you can hear him softly talking

through his two worlds you also live between,

a question in Hochdeutsch, a mutter of Bloomsbury slang,

a whistle of Brahms curving pure as aerodynamics

down the turn of the darkened stairs

where streetlight silvers the television screen

like the silence that passes over,

but says something all the same."

The Color of the Ghost, Sonya Taaffe

Though the poems mourn the silence and unknowing of the dead, the dead leap to life to speak anyway, when given the chance, and they are always saying something, in the end, whether we hear them or not. We may know the dead well enough to love them. We can, in turn, be loved back. These poems, for all their plaintive, somber qualities, are also full of light: lovers reunite, companions are found, once-silent voices sing (even if their songs are not the ones we wanted). In Ghost Signs, the final poem of the collection, the journey to the underworld ends with an emergence back into the world of the living, where knowing the dead is a part of being alive, that confronting our mortality and the ways in which we are already dead may bring healing and closeness with others.

A few of these poems jumped out and became favorites of the collection, and I am still thinking about them days later. I read The Road To Volodnye (Partisan's Song) and felt the immediate need to share it, so not to carry what is heavy in that poem alone. The Clock House, about Christopher Morcom and Alan Turing (originally published in Stone Telling, for longtime readers) is a poem I keep wanting to share with everyone. The aforementioned The Color of the Ghost and Lucan in Averno round out my favorites, along with Danger UXO, one of several poems themed around World War One. But there were no poems I found didn't belong in the collection or which felt particularly weak to me. The poems all flow into each other thematically and lyrically, though there is some stylistic difference between the scattering of sparse Russia-themed poems, the most overtly speculative poems in which modern cities bristle full of specific ghosts, and those that address the ancient world. These latter poems, which are the bulk of the collection, reward either a comprehensive knowledge of Greek and Roman literature, or strategic googling to catch the numerous mythic and historical references so as to really sink into the layers in which these poems converse with the past.

The story at the end, The Boatman's Cure, is more explicitly speculative than most of the poems, about an attempt to send the lingering dead away, and the ways in which one may be haunted. For this short story, readers should be aware of themes of suicide and violence, and for the collection as a whole, additional non-graphic mentions of war crimes and war in general. For long-time fans of Taaffe, this short story and two poems are the only previously unpublished work, though even for those who know and love these poems already, seeing them arranged together is an experience unto itself that is very much worth having. If you don't already love Sonya Taaffe's work, this collection makes a beautiful introduction.