There is That Line Again: Revealing the Pantoum in Context

by Deborah J. Brannon

Butterflies sport on the wing around,

They fly to the sea by the reef of rocks.

My heart has felt uneasy in my breast,

From former days to the present hour.

They fly to the sea by the reef of rocks.

The vulture wings its flight to Bandan.

From former days to the present hour,

Many youths have I admired.

The vulture wings its flight to Bandan,

Dropping its feathers at Patani.

Many youths have I admired,

But none to compare with my present choice.

His feathers he let fall at Patani.

A score of young pigeons.

No youth can compare with my present choice,

Skilled as he is to touch the heart.

William Marsden first translated this Malay pantun into English in A Grammar of the Malayan Language. [1] One of several such volumes Marsden wrote studying the government, culture, and language of Sumatra (where he spent the better part of a decade as an employee of the East India Company and then the government), he published this analysis of the Malayan language in 1812. [2] This pantun is a characteristic elaboration of the form, replete with allusions to a specific romance, images from nature, and geographical references.

Seventeen years later in 1829, Victor Hugo published Les Orientales, a collection of poetry inspired by the Hellenic war of independence. [3] He appended extensive notes to this collection, including many pieces of poetry by others and one of especial interest to students of the pantoum. In the notes specifically for "Nourmahal-la-Rousse," he printed a French translation of a Malay pantun from his correspondence with Ernest Fouinet. [4] Described only as an Orientalist and poet in the minuscule biographical notes available, [5] Fouinet is often credited with the inception of the French pantoum due to Hugo's inclusion of what he titles simply "Pantoum Malai." (Hugo himself is often largely credited with the popularization of the pantoum, along with Charles Baudelaire.)

The "Pantoum Malai" in question is actually a pantun berkait, a longer pantun set of interlocking quatrains. It is, in fact, a French translation of the same poem published years earlier in English by William Marsden. Despite the coincidence, it is possible that Fouinet's translation is as fresh from the Malay as Marsden's English verse was, considering France's long-standing preoccupation with the East in literature, art, and philosophy. [6]

I. The Pantun

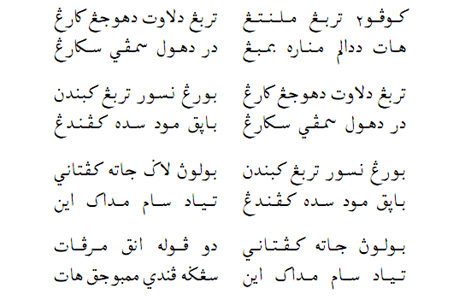

The Malayan pantun in Jawi script that was later translated by William Marsden

and Ernest Fouinet into English and French respectively. [7]

The pantun is an incredibly rich and storied poetic form in the Malay language; while originally an oral tradition in folk poetry, the pantun can be traced back to the fifteenth century in Malay literature through the Hikayat Hang Tuah and the Malay Annals. In the Annals, pantuns are used to demonstrate how historical narratives are clothed in the allusive properties of the form. [8] In the Epic of Hang Tuah, pantuns most often appear as romantic verses provoking desire. [9]

A pantun is a quatrain with an ABAB rhyme scheme. [10] As Burton Raffel observes in Development of Modern Indonesian Poetry, the quatrain is composed of two self-contained couplets capable of greater nuance than is attainable with the same four lines in English. He continues: "A pantun's first couplet is usually bold and sweeping; the second couplet shifts the focus to some more specific, more personal image, related to that introduced in the first lines, but subtly, often very subtly." [11]

Kūda pūtih ētam kukū-nia

Akan kūda sultān iskander

Adenda ētam bāniak chumbū-nia

Tidak būlih kāta īang benar

A white horse whose hoofs are black,

is a horse for sultan Iskander.

My love is dark, various are her blandishments,

but she is incapable of speaking the truth.

Marsden included this pantun in A Grammar of the Malayan Language as part of his explication on the measure of a pantun's lines: each line is composed of at least eight syllables, with lines of nine or ten syllables being deemed the most perfect. This is perhaps informed by the oral tradition of the pantun, with lines of those lengths being the most aurally pleasing.

Būrong pūtih terbang ka-jātī

Lāgi tutūr-nia de mākan sumut

Bīji māta jantong āti

Surga de-māna kīta menūrut

A white bird flies to the teak-tree,

chattering whilst it feeds on insects.

Pupil of my eye, substance of my heart,

to what heaven shall I follow thee? [12]

Both Raffel and Marsden discussed the incredibly subtle connection between the first couplet and the second in a pantun, and each of these examples from A Grammar of the Malayan Language showcase this incredibly well (at least to those not steeped in the Malayan language, culture, and literature). While the pairing of these couplets in each pantun feels ineffably right to me as a reader of poetry, I am hard-pressed to provide an explicit critical analysis of the unifying elements.

As evidenced by the pantuns above, the focus of many pantuns tends to be romantic or sentimental. Proverbs celebrating common wisdom are another recurring theme, however, as evinced in the following piece:

Bukan tanah mendjadi padi,

Kalau djadi, hampa melajang.

Bukan bangsa mendjadi hadji,

Djadi hadji tak pernah sembahjang.

This soil is no good for rice,

But if it grows, the wind will blow it away.

He's not the kind of man who should be a hadji,

Because now that he's a hadji he never prays. [13]

The blueprint for the Western pantoum is the pantun berkait, an interlocking set of quatrains with strictly proscribed repetition.

II. Birth in Translation

Hugo was delighted by the French translation of the pantun that Fouinet sent him, immediately including it among a random sampling of poetry in the notes to Les Orientales and describing it as "d'une délicieuse origanlité." This proved the pantoum's seeding ground, inspiring French poets to try their hand at the interlocking quatrains. Théodore de Banville, a poet well-known for reviving poetic forms such as the triolet, was one such poet. His work with the pantoum, in fact, codified the form as he honored the repetition of the pantun berkait and then chose to repeat the first line as the last, allowing for a more tightly woven whole.

Théodore de Banville published his first pantoum in 1857, a comic number entitled "Monselet d'automne," which appeared in Odes Funambulesques. [14] While he later published Petit Traité de Poésie Française (theories of versification) and chose a different poem to embody the concept of the pantoum, the playful tone in "Monselet d'automne" inspired British poet Austin Dobson to write a similarly whimsical piece entitled "In Town" in 1873. [15]

The French form was carried on by Louise Siefert (1868), Leconte de Lisle (Poémes Tragiques, 1884), and, most famously, by Charles Baudelaire with his "Harmonie du Soir" (1857).

Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige

Chaque fleur s'évapore ainsi qu'un encensoir;

Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Chaque fleur s'évapore ainsi qu'un encensoir;

Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu'on afflige;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir.

Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu'on afflige,

Un coeur tendre, qui hait le néant vaste et noir!

Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir;

Le soleil s'est noyé dans son sang qui se fige.

Un coeur tendre, qui hait le néant vaste et noir,

Du passé lumineux recueille tout vestige!

Le soleil s'est noyé dans son sang qui se fige…

Ton souvenir en moi luit comme un ostensoir! [16]

Baudelaire's pantoum does not honor the ABAB rhyme scheme of the traditional Malay influence, nor does it adopt the concept of ending the poem with the first line of the piece. However, it does strictly follow the scheme of line repetition, and features an ABBA rhyme scheme. In true pantoum tradition, if you remove the repetition from Baudelaire's "Harmonie du Soir," the piece falls apart. [17]

There are very few notable pantoums in English, apart from the aforementioned "In Town" by Austin Dobson. American poet Brander Matthews published "En Route" in Scribner's in July 1878, followed by Clinton Scollard's "In the Sultan's Garden" printed in his Pictures in Song (1884). British poet John Payne wrote a rather long pantoum entitled "Pantoum" in the late nineteenth century, the final stanza of which simply transposes the first and third lines of the first stanza into the second and fourth lines of the final quatrain with no inversion. There are a handful of modern poets who have published pantoums, including Donald Justice with "Pantoum of the Great Depression" and Nellie Wong's "Grandmother's Song" (both published in The Making of a Poem, edited by Mark Strand and Eavan Boland). Justice's poem in particular uses the pantoum form to stirring effect with prosaic doggedness. Of course, one of the better known pantoums in popular culture may be Rush's "The Larger Bowl" from Snakes & Arrows (2007). [18]

III. The Pantoum

The pantoum, as it stands today, is formulated thusly:

The poem is composed of a series of quatrains with carefully organized repetition throughout and an ABAB rhyme scheme. There is no set number of stanzas required. The second and fourth lines of the first stanza are repeated as the first and third lines of the second stanza, continuing in this manner for each successive quatrain: that is, the third stanza would use the second's second and fourth lines as its first and third, the fourth stanza would take it's first and third lines from the third stanza, and so forth.

This pattern is only broken in the final quatrain, which uses the preceding stanza's second and fourth lines as usual but uses the third line of the first stanza as its second line. The entire pantoum then concludes with the very first line of the poem also as its last. [19]

The pattern of the pantoum would look something like this, whereas the number represents line repetition and the letter keys you into the prescribed rhyme scheme:

1 A

2 B

3 A

4 B

2 B

5 C

4 B

6 C

5 C

7 D

6 C

8 D

7 D

9 E

8 D

10 E

9 E

3 A

10 E

1 A

Poets writing pantoums can achieve variance in meaning even in such a rigid structure by redistributing punctuation, and crafting lines wherein the meaning can inherently shift depending on its relation to the lines around it.

Austin Dobson was mentioned earlier as a British poet who wrote one of the first pantoums of some renown in English. His whimsical piece features a man driven nearly mad by a bluebottle fly and is nearly a perfect example of the form:

"The blue fly rung in the pane." — Tennyson.

Toiling in Town now is "horrid,"

(There is that woman again!)—

June in the zenith is torrid,

Thought gets dry in the brain.

There is that woman again:

"Strawberries! fourpence a pottle!"

Thought gets dry in the brain;

Ink gets dry in the bottle.

"Strawberries! fourpence a pottle!"

Oh for the green of a lane!—

Ink gets dry in the bottle;

"Buzz" goes a fly in the pane!

Oh for the green of a lane,

Where one might lie and be lazy!

"Buzz" goes a fly in the pane;

Bluebottles drive me crazy!

Where one might lie and be lazy,

Careless of town and all in it!—

Bluebottles drive me crazy:

I shall go mad in a minute!

Careless of Town and all in it,

With some one to soothe and to still you;—

I shall go mad in a minute;

Bluebottle, then I shall kill you!

With some one to soothe and to still you,

As only one's feminine kin do,—

Bluebottle, then I shall kill you:

There now! I've broken the window!

As only one's feminine kin do,—

Some muslin-clad Mabel or May!—

There now! I've broken the window!

Bluebottle's off and away!

Some muslin-clad Mabel or May,

To dash one with eau de Cologne;—

Bluebottle's off and away;

And why should I stay here alone!

To dash one with eau de Cologne,

All over one's eminent forehead;—

And why should I stay here alone!

Toiling in Town now is "horrid."

[20]

Dobson doesn't repeat the third line of the first stanza as the second of his last stanza, however. Indeed, from its very inception in Western poetry, the pantoum has been characterized by its adherents breaking the suggested rules as much as following them. Théodore de Banville may have attempted to formalize this poetic form inspired by the pantun, but poets from Baudelaire to Dobson to Rush's Neil Peart have shown that the pantoum is more a collection of characteristics than an inflexible form. The pantoum is an invitation to whimsy with its dance of advancing four lines only to retreat two, lulling the recipient into a hypnotic experience that is pleasurable as much for its do-si-do as its promenade.