Sewing Souls With Blanks: Silences in Kamala Das's Poetry

by Jaded

Two years ago, while studying Women's Studies in my Liberal Arts college in Mumbai, whenever we spoke of 'feminist' poetry it was Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, Emily Dickinson and towards the end of the year, some works by June Jordan too — diverse curriculum after all! — but mostly it was Dead White Women we spoke of. Of course, in our Literature courses there was one poem by Kamala Das and another by Eunice D'Souza, but somehow in Women's Studies, we didn't discuss them as much. As if, these two classes were two different shelves — in Literature we'd read Mahashveta Devi and talk about the Subaltern, about Indian English and 'postcoloniality' and in Women's Studies we'd talk about the Waves of Feminism (in the West) — and along with these shelves, we adopted our different selves, which must never merge.

We didn't realise at the time, but Feminism was ritually constructed by us on the words of women whose lives were so radically different from ours, and with invisible threads we sewed — or tried to — our lives together: a few white women giving words to a few brown women, and for a while it worked. Inevitably, huge gaps in the text would leap out, silences that would occur before the silence in the text, but I learned to not think of them too much — because after class I could come home and escape away in words that I could understand, in silences that felt like mine.

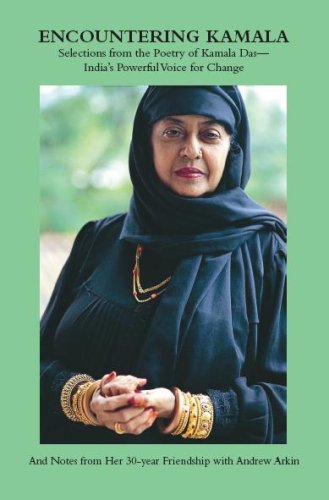

The cover of Encountering Kamala, edited by

Andrew Arkin, with photograph of Kamala Das

I have a few collections of poetry that were once my grandmum's, others I collected from second-hand bookstores — some on an impulse, some from whatever I remembered from my conversations with her — and poetry became a space I could slip into at will. Whenever it came to "answering poetry questions" in exams, I'd get confused — to an extent still am — for how do I "answer" a question that asks me about one of the very few spaces I don't feel Othered by, and still expect an answer in the impersonal tone? Especially words that Kamala Das wove around me, I find I cannot speak of her without writing about me, in some way or the other. As she wrote in her autobiography My Story, "[poets] cannot close their shops like shopmen and return home. The shop is their mind and as long as they carry it with them they always feels its pressures and torments" [1] as readers too, we cannot dis-engage with who she is as a person, the position she occupied, the space she created with her words and see how we figure in this mix, whether we fit in at all today.

Kamala Das, born Kamala Surayya, was born in a middle-class home and married into the Nayar community which allowed her to enter the elite literati of Malayalam literature. More often than not, colloquially, Kamala Das is called the 'Sylvia Plath of India' as both dabble with confessional poetry, both are relatively privileged in their own contexts; but one thing that holds Das apart is her awareness of lines and margins, specifically the ones she shouldn't cross.

Something I take in when reading Das is how each context is different, how each space and mood she inhabits is different and I too — as reader and re-writer of her thoughts within mine — must contort myself to these shifts. In "An Introduction" [2] she writes,

"…Why not let me speak in,

Any language that I like? The language I speak,

becomes mine, its distortions, its queerness,

all mine, mine alone.

It is half English, half Indian, funny perhaps, but at least it is honest

it is as human as I am human, don't

you see? It voices my joys, my longings…"

And the English I read with her becomes mine, as the tongue forms words she wrote. I didn't realise she was 'Indianising' English as Nessim Ezekiel argues in Culture, Colonialism and Indo-English Poetry, at the time, I didn't see Das as a "Writer as a historical witness", I saw her as a poet whose words sound like mine do, a writer who speaks of inner courtyards and women-spaces, a lingo I am familiar with because we're both Hindu women [3] as if she's passing shared cultural codes. The Western Feminists we studied at college expressed an anger for being left out of freedom, for not having the choices their male-counterparts did, while that anger made sense it didn't fit. For many of us, cultural norms dictated that we put the family and 'honour' before individual freedom irrespective of gender, so this anger didn't fit, so when Das was writing, her words don't bite against feeling excluded, rather at being voiceless.

As K. Lalita and Susie Tharu point out in Women Writing In India (Volume I), "Ideologies are not experienced or contested in the same way from different subject positions" [4] while reading Das became my refuge, it isn't a perfect text that voices every voiceless body. So many "universal" texts boast of doing and speaking for, but Das's writing remains rooted in her self-awareness, of bodies and borders. Being an upper-caste Hindu poet for most of her writing career, Das only maps and charts her body, the space her body carries is politicised but the Others in her works — anyone who doesn't hold the privileges she does in the caste and class hierarchy — aren't written out of the text, rather their presences are re-presented to us with silences.

Dalits and Muslims, factory works, workers in the fields from Das's own estates feature within these silences, and the text is careful to not chart the poet's [5] silence within these Others, for the oppression and marginalisation faced by Das and these Others is extremely different — be it class-wise or caste-wise from the doubly colonised Dalit body's point of view which faces oppression because of its position in gender and caste hierarchies [6] — and Das doesn't step over voices, neither her multiple silences nor theirs. A significant part of her works play with these silences, hers alongside the Others; in a way both become their own Subalterns — Das with her 'dark Dravidian skin' in a family of Brahmins, the Others occupying multiple and varying positions alongside and within margins of society's caste and gender hierarchies — and these Subaltern(s) are usually left silent, or passive.

In "Evening At The Nalapat House" [7] she writes,

"The field hands,

Returning home with baskets on their heads,

[…]

their thin legs crushing,

the heads, the shrubs, their ankles,

bruised by

Thorns, their insides burning with memories"

making me — the reader — aware of the Others' silence, without casting judgment. But when it's her own silence that she weaves into words, Das is cryptic, abrupt and sarcastic. In "The House Builders" Das writes,

"…Honour was the plant my ancestors watered

In the day, a palm to mark their future pyres at night their serfs

Let them take to bed little nieces" [8]

leaving no doubt that 'honour' for the Nayars — the caste Das's in-laws belonged to — meant sexually exploiting the lower castes, while shaming 'their' women for being overtly sexual, or for being bodies with sexual agency. Though these poems were written in the early 60's, not much has changed when we look at position of the Poet's Self, the Others and the Reader — for many of us Das's word re-affirm a well-kept secret of double-standards and societal hypocrisy that no one mouths out loud. Even as meta-commentary, "The House Builders" serves as an important moment in Indian memory; the 60's and 70's are remembered in mainstream-nationalist re-collection as the years of Nehruian utopic vision of 'success', rather Das talks of the underbelly of the 'upper echelons' society whose foundation works on the exploitation of anyone below them.

What fixes me till this day is Das's play with doubled silences, hers and the Others. She poignantly remarks in "Nani",[9] where the Dalit maidservant Das remembers from her childhood days commits suicide,

"…and I ask my grandmother

One day, don't you remember Nani, the dark,

plump one who bathed me near the well? Grandmother

Shifted her reading glasses on her nose

and she stared at me. Nani, who is she?

With this question ended Nani"

and no blanks are filled. Her grandmother comes to symbolise the 'old' feudal regime and a colonial system that leaves a silent presence, Das's child-persona is wise enough to not pry more and Nani's body is left politicised, in turn ask me to probe further. Many Dalit women working in Nayar houses would be sexually exploited and 'disposed off', in order to protect the family's 'honour'; Nani's death is similarly a play-act the Nayar caste puts up. While Nani's silenced body induces pity, Das doesn't over-step and speak or dislocate the fury a Nani would feel; similarly in her poem "Lunatic Asylum" [10] she notes,

"…No

Do not pity them, they

Were brave enough to escape, to

Step out of the

Brute regimentals of

Sane routine, ignoring the bugles, the wall

of Wens"

where the a-politicised bodies of the 'lunatics' gain a space in the border of semantics, where They — the Others — are seen in their own right, in relation to terms and spaces she knows best, of being confined and bound by patriarchy — her infamous line, "I am now my own captive" signifies this cycle of confinement, and leaves gaps of silence.

Though her work signifies the Silences of the Others, she doesn't try to fill them — in turn warning me to not speak for them either. While her doubled silences represent to us doubled margins, they do so while co-existing and not as echoes of one another — something Western Feminism has yet to teach me. Sometimes, it's more than cathartic to be given a space, like Das builds where either the text or the silences in the text don't stretch over edges, to the extent of engulfing all voices located on margins and in cracks between spaces, between silences — once again, showing ways of resisting that don't require writing over voices.

Slipping my silence with Das and Das's Other-ed bodies doesn't forge bonds between us of solidarity or similarity; rather it is of a co-exiting difference, where each silence roars in its own way.