In Search of Truth and Beauty within the Intersection of Multicultural Myths and Poetry

by Emily Jiang

I remember the day my fifth grade drama teacher read aloud to my class the magically illustrated Book of Greek Myths by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaires. Previously, my exposure to the mythic had been limited to Bible stories I learned attending Sunday school right after Chinese school and random stories my dad would tell me about the adventures of the Monkey King.

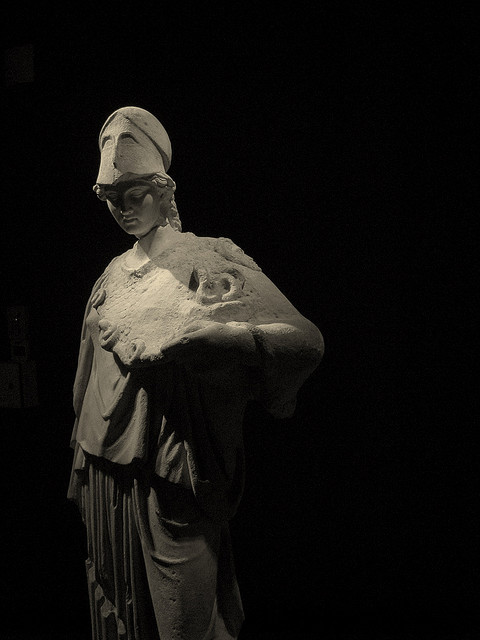

A statue of the Greek goddess Athena

photograph by Soham Banerjee

But Greek mythology was marvelous, wondrous, to me because the gods themselves were not all-knowing, all-seeing, all-perfect. The gods had limitations and desires like human beings, and behaved very badly, often resulting in an abundance of origin stories. So many stories! After I was exposed to Greek myths, I read every mythology book at my local library; Greek and Roman myths were my favorite, followed by Norse myths, followed by Egyptian myths. When I finished those books, I started reading every fairy tale collection at my library, especially Andrew Lang's series of color Fairy Books. When I finished those, I started reading science fiction and fantasy, which I still read to this day.

Thus, my love for fantastic stories is firmly rooted in mythology, specifically Greek mythology, which may surprise complete strangers who take one look at my face and think I should know more about Asian myths, ironically—or not ironically at all since I was born and raised in the United States. During my childhood myth-researching phase, I could not find more than a handful of books on Asian/Chinese mythology in the library, and what I did find was nowhere near as well written or well illustrated as the D'aulaires' Book of Greek Myths.

Like characters, godsare so much more compelling

when they're imperfect.

Once upon a time, there lived a girl who loved poetry, but only Chinese poetry, especially that written by Li Bai. She loved reciting poems, reveling in the simplicity of short lines, the compactness of words, the sounds of its rhymes. She was repelled by the weird whimsy of Dr. Seuss (who fancied himself a poet more than an illustrator); in fact, she hated The Cat in the Hat for his destructive and chaotic qualities, as she could not make sense of any of his words. She was baffled by the riddles of Where the Sidewalk Ends, also written (and illustrated) by a poet-artist, Shel Silverstein. She believed poems written in English to be overly wordy and fussy with impossible descriptions, from the self-centered Whitman to the romantically long-winded Wordsworth. But then, her fourth grade teacher taught a poetry unit on Robert Frost. This girl loved his poems. She thought his straightforward phrasing and his focus on nature reflected her own aesthetic.

Whose words these are, Ithink I know—his house floats on

moonlight, miles to go.

INFLUENCES

Her own aesthetic sparked in English, this girl went in search of poetry written by poets who were not dead or nearly dead white men. She read the works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sara Teasdale. This girl also discovered two other Emily's who were writers, and she loved Dickinson, not Bronte. Bronte was too unruly, too irrational, and too wild for this young Emily's rather particular reading tastes. However, if you ask older Emily now, you might get a different answer—or the same—who knows really. Older Emily has studied poetry ranging from required reading British authors Chaucer and Shakespeare to American confessionals Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, and Anne Sexton. She searched for the unique voices of multilingual poets Gloria Anzaldua and Derek Walcott, contemporary Chinese poets Shu Ting and Bei Dao as well as Asian American poets Timothy Liu, Li-Young Lee, David Mura, and Arthur Sze. However, some of her favorite poems were not originally written in English but Romanian (translated by Seamus Heaney), and contrary to her child self, she adored the whimsy of Marin Sorescu's work.

Daguerreotype of the poet Emily Dickenson

taken circa 1848

But no matter how many poems she read, this girl was still inspired by Emily Dickinson and her obsession with Truth, Death and Beauty. Like Emily D, she contemplated Death as character. Like Emily D, she believed in the existence of absolute Truth. Unlike Emily D, she struggled with Beauty, as she found it difficult as an Asian growing up in Texas to hold herself to just one standard of Beauty. Nevertheless, this girl loved the idea of creating in solitude, writing reams of poems, never caring if anyone will ever read her work.

I'm Nobody, whoAre you? Are you No One, too?

Slave to Beauty, Truth.

The goddess whom I found most compelling is Athena, the Greek goddess of war and weaving and wisdom. War, strategy or otherwise, is traditionally a male-dominated area while weaving is typically viewed as women's work, yet this one goddess embodies both, as well as wisdom. I was especially intrigued by Athena's origin story, as she sprung, fully grown, fully armored, out of her father's head.

Another mythological character who absolutely fascinates me is the Monkey King. Like Athena, Monkey King had an unusual birth, only he leapt fully grown out of a stone. Like Athena, Monkey King was a master of many powers, though his were more concrete—surfing a cloud, transforming his shape, and fighting. Unlike Athena, he often chose violence as a way to resolve his problems in the most direct manner possible. He fought his way to become King of the Monkeys, yet as Monkey King he still found himself with servant status to the gods living in Heaven. Thus, he battled the armies of Heaven and Earth, and he even dared to challenge the Buddha.

Like Athena, my personal construction of self incorporates the juxtaposition of opposites. As the daughter of Chinese-American immigrants, I grew up speaking two languages and living in two polar opposite cultures and learning to mesh them in harmony within myself, while, like Monkey King, struggling to find my place in a society that did not appear to be similar to me. Raised in Texas and now living in California as an adult, I found the assimilation of the cultures of these two vastly different states to be an extension of my hybridization experience as a child.

Was my sense of self directly influenced by Athena and Monkey King, or was I drawn to them because they evoked the extreme dichotomies in my life? I'm still not sure.

Within my mind livesa grey-eyed goddess guiding

a stone-born monkey.

INSPECTING SOURCES

The Monkey King in a Beijing opera performance

photograph by d. FUKA

While my first source of Monkey King stories was my father, who probably heard it from his father or mother, what grounded my knowledge of this most famous Chinese myth was reading English translations. For years the major text in English that addressed the story of the Monkey King was Monkey: Folk Novel of China by Wu Ch'eng-an, translated by Arthur Waley, who was an English orientalist. As a child, I read this book several times, but have yet to revisit it as an adult. Now there are many, many English versions of Monkey King's story, also known as Journey to the West.

As an adult, I am aware how incredibly U.S.-centric my views of mythology have been and still are. As an English major at an American university, I discovered my knowledge of Greek mythology helped me with the ubiquitous literary allusions found in British and American poetry and fiction. Once upon a time, those who were educated in the English language were required to master knowledge of Greek mythology, as well as a smattering of French and Latin. But what I find most ironic is that Americans like myself and Joseph Campbell, who know Latin but not Greek, have often appropriated Greek mythology by reading translations that were originally appropriated by non-Greek Europeans like the d'Aulaires, who were technically European-American since they immigrated to and published in the United States. This double appropriation of Greek mythology is something that is not commonly acknowledged, at least not in the American mainstream.

Translations: What's lostwhen you cannot read, speak

original texts?

As an adult, this solitary poet girl discovered that Emily D was not as isolated as legend would suggest. But then isn't legend sometimes more True than fact. Isn't Truth part of myth, part of poetry?

Because I could notstop for Truth, it kindly stopped

my reality.

ORIGINS: THE SPOKEN WORD

Time to entwine the threads of myth and poetry; I find the roots in oral traditions, as simple as the parent telling a bedtime story to a child, as I had originally learned of the Monkey King, or going back thousands of years to when The Odyssey, a mythic epic poem, was retold from poet to poet in a multigenerational game of Telephone.

Once upon a time =Once up a time = Once up time =

One up = Wassup?

As an adult, this poetry-loving girl had the opportunity to hear seasoned poets recite their works. She observed Adrienne Rich, age of almost 80, walking so carefully using her bright red walker, yet Rich's voice boomed and fired through her listeners with the power of a tsunami. She was lulled by the almost sing-song quality of Brenda Hillman asking big, complicated questions. She listened to the purposeful silences of Arthur Sze. She was blown away by the rousing passion of Lee Bennett Hopkins and the play of Ashley Bryan singing a call-and-response of his poems with an audience of a thousand.

Perhaps the most memorable reading this girl had ever experienced was meeting Robert Bly, one misty morning at the end of a mountain retreat, where he read poetry to her and her alone. When he read poetry, his eyes transformed to blue fire, and the richness of his voice threatened to melt her bones. The poems were not his, but Rumi's, written hundreds of years ago. Oh, the lasting power of words.

Tell me your strange Truth:Speak to me of Death, Beauty,

Love and Poetry.