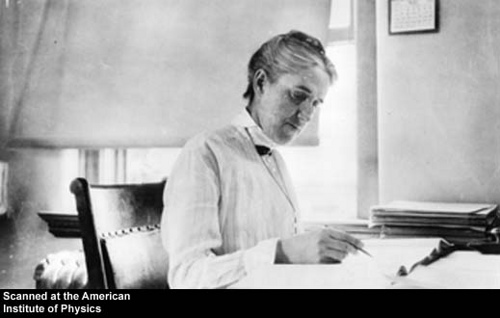

[HOME] [ISSUE] [ARCHIVES] [ABOUT] [GUIDELINES] [BLOG]  Girl Hoursby Sofia SamatarFor Henrietta Swan Leavitt Notes In the 1870s, the Harvard College Observatory began to employ young women as human computers to record and analyze data. One of them, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, discovered a way to measure stellar distances using the pulsing of variable stars. Quotations are from George Johnson's Miss Leavitt's Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe (W. W. Norton, 2005). Harlow Shapley, director of the observatory, reckoned the difficulty of astronomical projects in "girl hours"—the number of hours a human computer would take to obtain the data. The most challenging projects were measured in "kilo-girl-hours." Conclusion You were not the only deaf woman there. Annie Cannon, too, was hard of hearing. On the day of your death she wrote: Rainy day pouring at night. Oh bright rain, brave clouds, oh stars, oh stars. Two thousand four hundred fires and uncharted, unstudied, the hours, the hours, the hours. Body The body is a computer. The body has two eyes. For the body, the process of triangulation is automatic. The body can see the red steeple of the church beyond the trees. Blackbirds unfold as they grow nearer, like messages. The body never intended to be a secret. The body was called a shining cloud, and then a galaxy. The body comforted mariners, spilt milk in the southern sky. The body was thought to be only 30,000 light years away. The body is untrustworthy. It falls ill. The thought of uncompleted work, particularly of the Standard Magnitudes, is one I have had to avoid as much as possible, as it has had a bad effect nervously. The body sits at a desk. A high collar, faint stripes in the white blouse. In this rare photograph, the body is framed in light. The gaze is turned down, the hand poised to make a mark. The body says: "Take photographs, write poems. I will go on with my work." The body is not always the same, the body varies in brightness, its true brightness may be ascertained from the rhythm of its pulsing, the body is more remote than we imagined, it eats, it walks, it traverses with terrible slowness the distance between Wisconsin and Massachusetts, the body is stubborn, snowbound, the body has disappeared, the body has left the country, the body has traveled to Europe and will not say if it went there alone, the body is generous, dedicated, seated again, reserved, exacting, brushed and buttoned, smelling of healthy soap, and not allowed to touch the telescope. The body gives time away with both hands. The body, when working, does not know that time has passed. The body died in 1921. The body's edges are so far from one another that it is hardly a body at all. We gather the stars, and we call them a body. Cygnus. The Swan. Introduction Twelve o'clock. My husband and children asleep. To chart one more star, to go on working: this is a way of keeping faith. Draw me a map. Show me how to read music. Teach me to rise without standing, to hold the galaxy's calipers with the earth at one gleaming tip, to live vastly and with precision, to travel where distance is no longer measured in miles but in lifetimes, in epochs, in breaths, in light years, in girl hours. Sofia Samatar is an American of Somali and Swiss-German Mennonite background. She has lived in Egypt and South Sudan, and is currently pursuing a doctorate in African Languages and Literature at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she specializes in twentieth-century Egyptian and Sudanese literatures. Her poetry is forthcoming in Bull Spec and the anthology The Moment of Change, and her debut novel, A Stranger in Olondria, will be released by Small Beer Press in 2012. She blogs about books, the Arabic language and other wonders at sofiasamatar.blogspot.com. Read Sofia's discussion of this poem over at the Roundtable! Photography: Henrietta Swan Leavitt at her desk, from the AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

|